Tackling Global Issues in Neuroscience Research

The large-scale national and regional brain initiatives are helping to propel neuroscience forward. But there are common and persistent challenges that neuroscience leaders need to address to realize the full impact of recent advances in brain research and technology. At its annual Coordinating Body Meeting, the International Brain Initiative brought together partners, funders and other stakeholders to discuss some of these challenges, including the need to support the next generation of neuroscientists and advance data governance internationally.

The IBI's 2021 Coordinating Body Meeting (2021 CBM) spanned two days in early December and brought together more than 70 neuroscience leaders from around the world. It was co-organized by the Australian Brain Alliance and The Kavli Foundation and designed to help the IBI identify and explore high-priority issues in neuroscience where the IBI and its partners could have an impact.

In addition to early career researchers and international data governance, the meeting also focused on political engagement to advocate for neuroscience funding and the commercialization of brain research. (View the meeting agenda, including speakers and panelists.)

Jump to:

Global Perspectives on Early and Mid-Career Researcher Networks

Keynote presentation by Dr. Mark Cook on the development of an epilepsy prediction device

Lessons on Political Engagement

On day one of the 2021 CBM, speakers from the European Union, Australia and Canada shared their experiences developing large-scale brain research strategies and engaging with policymakers to drive support for those strategies.

Linda Richards, Head of the Department of Neuroscience at Washington University in St. Louis and former chair of the Australia Brain Alliance (ABA), emphasized that influencing policymakers requires constant engagement. Relationships with government take time to build, require maintenance and may require renewal due to high turnover in policy circles. She also recommended researchers view the relationship as a partnership, where researchers and policymakers can explore the common interests of science, society and government.

The ABA was founded in 2016 to secure government funding for an Australian Brain Initiative. Since then, it has garnered the support of government and non-governmental organizations across Australia, established an early and mid-career researcher network and driven the development of large-scale bioinformatics and data infrastructure for neuroscience.

Before engaging with policymakers, the ABA's leadership focused extensively on building consensus on research priorities in Australian neuroscience. Richards stressed the importance of delivering a clear, unified message to policymakers and said that identifying priorities for the field and how those aligned with the needs of society was the most challenging part of the process for the ABA.

"You can't have five neuroscience groups going to government with separate agendas," she said, adding that you must have a clear "ask" and be able to justify it.

The ABA developed a business case for an Australian Brain Initiative. It articulated the Initiative's goals and potential outcomes, including its potential impact on research, health, education, and the economy. "We outlined what the impact would be broadly on society," said Richards.

The business case was also specific and costed, she said, and ultimately had the most significant impact on policymakers.

Following Richards, Jennie Young, Executive Director of the Canadian Brain Research Strategy (CBRS), presented the organization's work toward developing a vision for a national brain research strategy. As with the ABA, CBRS has focused on bringing together stakeholders to reach a broad consensus on what a Canadian brain initiative should look like. CBRS has prioritized early career researchers, Indigenous researchers, and patients among those stakeholders.

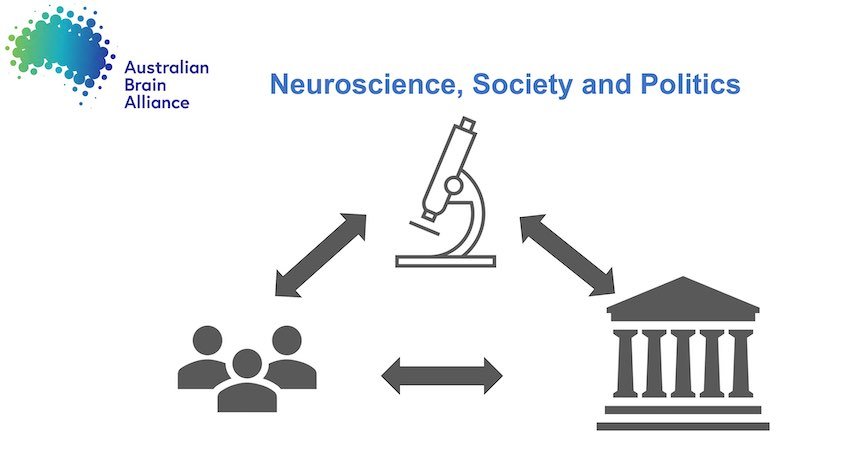

The organization has identified Canada's unique brain research strengths, which are collaborative, transdisciplinary and open, with the goal of "inspiring the government to build on these strengths," said Young. CBRS has also identified six focus areas, called "transformational initiatives," where Canada could be both a leader and a role model internationally. They include open science, neuroethics and the intersection between neuroscience and artificial intelligence.

Moving forward, the CBRS will write a position paper for each transformational initiative based on a series of researcher roundtables and multi-stakeholder workshops. It is using a three-part framework to build a case for investment in brain research: Inspire, Guide and Forecast. Specifically, the organization aims to highlight urgent and unique opportunities to advance brain research in Canada that play to the nation's strengths, specify the resources and activities needed to build on those strengths, and envision the potential impact of a Canadian brain initiative on research and society.

Jan Bjaalie, chair of the IBI's strategy committee and a member of the Human Brain Project (HBP) Directorate, also emphasized the need for long-term planning and patience. He said that many of the successful European Union (EU) research programs happening today have a 20-year history. The EU has a 5-year funding cycle, plus an additional 2 years for planning. "As Linda [Richards] said, yes, you have to pick your moment. But you have to do it long before you have the need."

European researchers have a variety of informal and formal channels they can use to engage decision-makers and influence research priorities and funding. He said work is underway on a roadmap to put brain health at the center of Europe's research agenda beginning in 2027, when the current Horizon Europe program ends, and that the community has ambitions around the creation of a European Brain Initiative.

The Next Generation of Brain Researchers

As a co-host of the 2021 CBM, the ABA decided to spotlight the needs of future leaders in brain research.

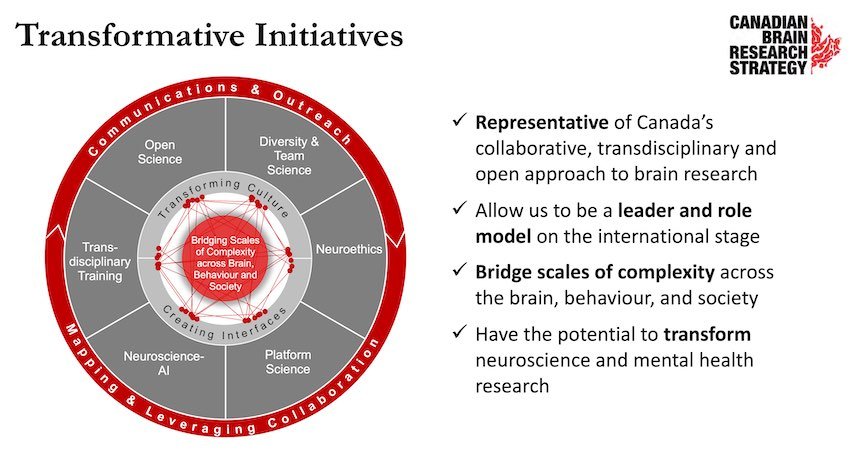

Hannah Keage and Bernadette Fitzgibbon co-chair the ABA's Early and Mid-Career Brain Science Researcher Network (EMCR Network). They provided a snapshot of the supports and barriers to career advancement faced by EMCRs and the role the International Brain Initiative and its partners could play in supporting EMCR development.

In preparation for the CBM, Keage and Fitzgibbon interviewed IBI-affiliated researchers in Australia, Canada, Japan, Nigeria, and the United States about career progression, key challenges and support structures.

They found that EMCRs face many of the same barriers to career advancement, but those vary by degree from region to region. For example, low success rates in funding competitions and a lack of job security are particularly problematic in some countries, specifically those that haven't adopted incentives to support ECMRs. Consequently, EMCRs are looking for employment opportunities outside of academia—a trend that COVID-19 has amplified.

"We've seen people achieve the impossible and then give it up," said Fitzgibbon. "They don't know how to sustain a career with no guaranteed way to sustain a research program."

At the same time, Keage and Fitzgibbon found that exposure to career opportunities outside academia, where PhDs are highly valuable and employable, is variable. Canada, for example, has funding programs to support training and research collaborations between industry and academia.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased pressures on EMCRs and reduced research productivity. For example, they presented data from the United Kingdom showing that researchers initiated fewer research projects and collaborations during the pandemic. This worrisome trend was particularly acute among female scientists and those with young children. Other data showed that more than 90 percent of researchers experienced mental health issues during the pandemic. Keage and Fitzgibbon warned that the research community has yet to feel the pandemic's full impact and that COVID-19 could magnify existing inequalities in science and jeopardize its long-term vitality.

Keage and Fitzgibbon concluded their presentation by proposing the creation of an IBI EMCR Network that could empower the global EMCR community and help shape the future of brain science. They envisioned a worldwide network that would facilitate communication across academia, industry and government, and help address systemic barriers affecting the next generation of brain researchers.

Moving Brain Research to the Clinic

Day Two of the CBM kicked off with an inspiring presentation by Dr. Mark Cook, Chief Medical Officer of Seer Medical and Chair of Medicine at St. Vincent's Hospital in Melbourne, where he specializes in the treatment of epilepsy. Cook described decades of research that have culminated in a seizure prediction device for individuals with epilepsy, especially people who experience drug-resistant seizures.

His research is an example of how basic research in neuroscience and technological advances are leading to neurotechnologies that are helping to alleviate the burden of brain disease.

Cook and his team have developed a system that uses real-world brain data to forecast seizures at least 90 minutes in advance. These personalized seizure forecasts allow people with epilepsy to make decisions about their daily activities and manage their medications.

"Knowing what seizure-free time they have is enormously liberating. Many of the people we've worked with have found it enormously empowering," said Cook, who is commercializing the technology through Seer.

Cook reflected on the factors that have led to its success, noting the importance of close collaboration between clinicians, scientists and engineers. He also said he has benefitted from strong institutional support, including his university's commercialization office.

While strong research partners are essential, he stressed the importance of tapping into outside expertise, such as reimbursement and regulatory experts. "They have a rare and essential expertise that scientists do not," he said.

Cook also commented on the essential role that patients and their families play in innovation. The earliest versions of his device were invasive and untested. Still, patients were willing to participate in the research because he was clear and transparent about what the research team aimed to achieve.

Unleashing the Power of Neurodata

To close the 2021 CBM, Judy Illes, Professor of Neurology at the University of British Columbia and Co-chair of the Canadian Brain Research Strategy, led a panel discussion on advancing international data governance rooted in neuroethical principles and how it could support scientific discovery and neurotechnology translation.

Panel participants Floh Thiels (National Science Foundation), Franco Pestilli (University of Texas at Austin), Ricardo Chavarriage (Confederation of Laboratories for Artificial Intelligence Research in Europe (CLAIRE), Zürich) and Tan Le (Emotiv) discussed existing models of data management. They also shared their views on how an ethically sound international data governance structure could spur discovery and innovation and how the IBI could help move such a structure forward.

The panelists described international data management as a heterogeneous and fragmented landscape that would benefit from better instruments and harmonization between regions. Existing models and platforms include federated data access, where users can access and use data stored in external databases. According to Le, data management at Emotiv, which spans 100 different countries, relies on personal identifiers. Ownership and control of their data rests with individual users who authorize and derive value from its use on a case-by-case basis. She suggested Emotiv's model for the management of human data could be scaled globally.

As large datasets accrue and are increasingly shared across borders, the panelists said an international data governance structure is essential to building and maintaining trust in science. "This field has the potential to transform lives and impact them for the better," said Le. But she cautioned that neurotechnology could suffer a "winter" similar to the AI winter of the 1970s and 80s if the field cannot find a way to unlock the knowledge trapped in large-scale data while also ensuring its protection.

Others said there is a moral imperative to develop regulatory standards and ethical recommendations for neuroscience data. On a more practical level, they said governance structures are needed to alleviate the burden and facilitate data sharing for research purposes.

The IBI has established a Data Standards and Sharing Working Group, including panelists Pestilli, Thiels and Chavarriaga, but it could do more to move the neuroscience community toward an international data governance structure, they said. Thiels urged the IBI to identify specific use cases, such as sharing EEG data, and identify roadblocks and strategies to overcome them.

Several panelists viewed the role of the IBI as the "glue" that could bring relevant international stakeholders together while acknowledging that international collaboration and coordination is difficult, in part because of a lack of funding and other incentives. The IBI could help mobilize institutions and organizations, identify gaps and tensions to be addressed, prioritize next steps and create incentives to fuel progress on international data governance.

Finally, Chavarriaga urged the IBI to learn from and contribute knowledge to similar data governance initiatives outside of neuroscience, such as AI and genetics.

"There is potential for the IBI to share the lessons that we've learned during this process and engage with the others. We can bring the vision from the worldwide neuroscientific community. We are at the point where we can have impact on shaping policies and governance," he said.